With the overall global pursuit of just and equitable economic development as well as sustainable progress, one area that has emerged into prominence is gender equality at birth and more broadly, empowerment of the girl child. The birth rate of the girl child, eclipsed in parts of the globe by skewed cultural as well as demographic considerations, plays a critical role in determining the nation’s future manpower, productivity, capacity to innovate, and overall well-being. The economic impact of having balanced girl child birth rates is not only critical to every nation but also has far-reaching implications for global human development capital, GDP growth, and economic vulnerability in the long run.

As of 2023, the sex ratio at birth worldwide stands at around 105 male births per 100 female births, a natural occurrence. But in countries like India, China, Pakistan, and parts of the Caucasus, ingrained patriarchal values have tilted this against women. In India, for instance, the number of children aged 0–6 years was estimated to be 918 girls per 1000 boys in the 2011 census, indicating a gender shortage of millions of “missing girls.” China experienced the same crisis, where the sex ratio was 121 boys per 100 girls in the early 2000s. Imbalances like these are not only social or ethical problems—They’re economic costs.

The United Nations Population Fund estimates that over 140 million women and girls are missing globally due to gender-biased sex selection and infanticide. It has long-term economic consequences. A lower proportion of females in the population implies less female labor-force participation, reduced consumer diversity, and a narrower base of entrepreneurs and skilled professionals. Moreover, gender unbalance can lead to more societal instability, e.g., increased levels of crime, human trafficking, and reduced marriage rates, all of which have measurable economic losses.

Conversely, increasing the girl child birth rate towards natural balance has yielded economic benefits. Countries that have made a transition towards gender equality of birth rates and invested in girls’ education and health have reaped substantial economic benefits. For example, Bangladesh, through sustained policy efforts in education and female welfare, achieved a parity sex ratio and witnessed a 50% increase in female labor force participation over two decades, contributing to an average annual GDP growth rate of 6–7% during the same period.

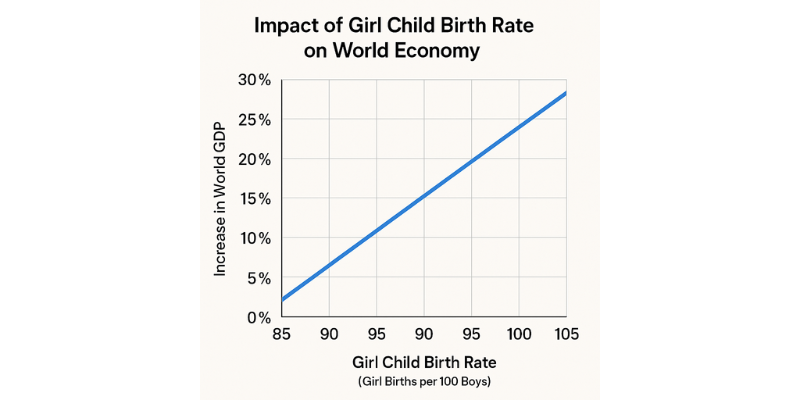

Girls born today are the workers of tomorrow, and an investment in their survival and development is a high yield policy. For emerging markets, each 1% rise in gender equality is accompanied by 0.3–0.4% GDP growth, according to World Bank estimates. In the event of gender parity in labor market participation in every nation, global GDP may increase by $28 trillion over the period from today through 2025, a 26% rise, according to McKinsey Global Institute.

With better girl birth ratios in economies, sectors such as education, healthcare, technology, and governance experience a ripple effect. For example, in Rwanda, where gender reform post-genocide focused on female life and leadership value, 64% of seats in parliament are occupied by women, and GDP in the country has doubled in the past 20 years. This linkage between birth gender equity and economic performance highlights the systemic relevance of redressing girl child undervaluation.

Demographically, gender-balanced populations ensure more balanced patterns of growth. Given that nations like Japan, South Korea, and Germany are confronting aging populations and low birth rates, the worth of each child, particularly girls, becomes essential to maintaining a productive workforce of working ages. Sex ratios distorted now may translate into shortages of workers in the future, particularly in industries like care, education, and social services where women predominate.

Education is also a changing driver. Increased education for girls has been shown in studies to increase future earnings by 10-20% for every additional year they receive. Education reduces child mortality and fertility levels. Valued, educated, and employed girls who are born become disproportionately contributing economic and social capital. If all girls completed secondary education, UNESCO calculates this could have more than $92 billion in economic benefits annually in low- and middle-income countries.

But to realize the full economic reward of higher girl child birth rates, there must be supportive policy stimulus. Conditional cash transfers like India’s “Beti Bachao Beti Padhao” have been shown to be effective in eradicating gender-based birth discrimination and increasing awareness. As South Korea’s reversal of skewed sex ratios was assisted by public education, reform of the law, and an economic narrative that valorized women’s contribution to national advancement.

Health access is also crucial. Keeping girls alive at infancy, healthy, and protected from child marriage or early pregnancy ensures their full potential. Anemia and malnutrition cut into over 40% of South Asian adolescent girls, inhibiting their long-term economic contribution, it is estimated. Investments in girl child health can thus boost future workforce productivity as well as reduce national healthcare expenses.

The digital economy, too, benefits from gender-equal societies. More girls surviving and entering the digital workforce can drive inclusive innovation. Female-founded startups in Africa grew by 40% from 2016 to 2021, and gender-equal digital participation will contribute over $300 billion to the African GDP by 2030. Extrapolating globally, balanced gender birth rates can close STEM skill gaps, drive diversity-led innovation, and reshape traditionally masculine industries.

Even with these promising developments, however, there remain barriers. Inheritance and property laws on the basis of sex, gender violence, and cultural sex taboos all still devalue the birth and upbringing of girls in most cultures. The national economic cost, in terms of foregone productivity, lower household incomes, and increased social unrest, overwhelms any perceived cultural gain.

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Goal 5 (Gender Equality) and Goal 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), also strongly support bringing an end to all forms of discrimination against girls, from birth. These can be achieved through multi-sector approaches—legal reform, strengthening the health system, subsidies to education, and mass media mobilization—to counter gender imbalance at the core.

Lastly, the survival and birth of the girl child are not only human rights issues—they are strong economic imperatives. A balanced sex ratio ensures an equal workforce, diversified economic inputs, and greater resilience and innovation. Countries that recognize girls’ economic value at birth are laying the foundations for a more inclusive, sustainable, and prosperous future. With all our hopes for global fairness, raising every girl child from birth could be the most profound investment we ever make in the global economy.

Prepared by

Sureshkumar Mandala

Assistant Professor, School of CS&AI,

SR University, Warangal, Telangana 506371

m.suresh@sru.edu.in